Module 2: How does my TBI affect me?

What does the brain do?

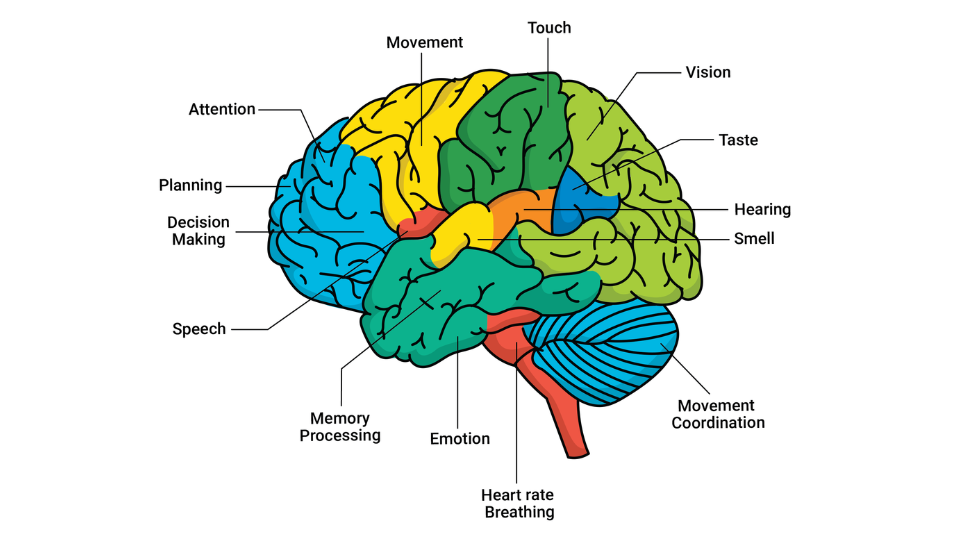

Each part of your brain has a specific function. This picture shows the main functions of each brain area. An injury can happen to any part of your brain. You may have injured a specific part of your brain (this is called a focal injury) or multiple parts of your brain (this is called a diffuse injury) (1).

When one part of the brain is injured, it makes it difficult for other parts to work. Your brain is like an orchestra. It has many small sections and all of them need to do their own work, and also work with other sections, to make music. If one section – for example, the strings – are not playing very well, then the overall music will not sound as nice.

This is what happens to your brain when you have a TBI. The area(s) of your brain that are injured do not work as usual and this in turn affects your overall brain function.

What difficulties might I have?

TBI is a heterogeneous (varied) condition (2) that can cause physical, cognitive, behavioural, and psychological difficulties. This means that no two TBIs are exactly the same. Each person has a different journey with their TBI, depending on which area(s) of the brain are injured and the severity of their injury. You may find it difficult to do some tasks that you used to do by yourself before.

Here are some examples of the difficulties you may experience:

Physical

- loss of balance and dizziness,

- experiencing seizures/epilepsy,

- changes to your senses like touch, sight, hearing, taste and smell

- headaches,

- difficulties with sleeping,

- fatigue, difficulties with walking,

- difficulties with toileting,

- difficulties with swallowing food and drinks safely,

- difficulties with moving your mouth to talk,

- sexual changes.

Cognitive

- planning,

- organising,

- attention and concentration,

- memory loss,

- learning new skills,

- difficulties in using correct words,

- understanding other people,

- motivation,

- difficulties starting and completing tasks

- making decisions,

- repeating a behaviour or speech.

Behavioural

- understanding why you are not allowed to do certain things on your own (e.g. shower or go for a walk),

- understanding what can be unsafe for you,

- controlling impulsive or inappropriate behaviours,

- difficulties in seeing from another person’s point of view (e.g. you may only have one way of looking at a situation),

- anger or agitation: You might be angry at yourself, the situation or people around you.

- Psychological stress,

- anxiety,

- PTSD (post-traumatic stress disorder),

- depression,

- suicidal thoughts,

- panic attacks.

Waking up to changes with your body

Waking up to find changes with your body can be strange or even scary. At first, many people with a TBI view their bodies as unfamiliar or not their own (3). Some people have even described their bodies as frightening or an enemy – something that fights against them or that could betray them at any time (4).

It can feel very scary not to be in control of your body.

It is still very early days since your injury. Your doctors and healthcare team will work with you to help you to understand which difficulties you have after your injury. After your condition has stabilised, you will also start some brief rehabilitation to work on recovering your functions.

There will be more on this in Module 3: What to expect in the early days of recovery.

Is TBI considered a disability?

In Australia, an individual is considered to be a person with disability if they have any medical condition which causes limitations or impairments which restrict their everyday activities and is likely to last for 6 months or longer (5).

These limitations may be physical, cognitive, behavioural or psychological.

While TBI is a leading cause of disability around the world (6, 7), not everyone with a TBI is considered a person with disability. This depends on the severity of the brain injury, how much and which areas of the brain were injured, and what the resulting limitations or impairments are. For some people, it can be upsetting to be labelled as a person with disability.

This may be due to grief and loss of your pre-injury identity, or struggles with accepting your new life. This may also be due to disability stigma in society.

Disability stigma is when someone has negative beliefs about people with disabilities. This may lead to social exclusion or discrimination. Stigma often lies at the root of discrimination and exclusion experienced by people with disability and can impact community integration following brain injury (8).

Stigmatising attitudes may need to be challenged by yourself and those around you to improve your relationship with your disability.

A person’s disability status can change over time. There are many factors that can decrease or increase your level of disability. Some examples are:

- Practicing important skills (e.g. dressing yourself or brushing your teeth),

- Moving regularly to strengthen your body and improve coordination,

- Setting goals that are important to you and sticking to them. It is possible to regain important abilities after brain injury with ongoing rehabilitation.

Questions to ask your medical team

To understand your TBI and how it will impact you, you can ask your doctors:

- Which part(s) of my brain has been injured?

- What function(s) do I have difficulties with?

- Is it likely that I will have a disability? If yes, how long is the disability expected to last?

References

- Andriessen TM, Jacobs B, Vos PE. Clinical characteristics and pathophysiological mechanisms of focal and diffuse traumatic brain injury. Journal of cellular and molecular medicine. 2010;14(10):2381-92.

- Covington NV, Duff MC. Heterogeneity is a hallmark of traumatic brain injury, not a limitation: A new perspective on study design in rehabilitation research. American journal of speech-language pathology. 2021;30(2S):974-85.

- León Carrión J, Machuca Murga F. Spontaneous recovery of cognitive functions after severe brain injury: when are neurocognitive sequelae established? Revista Española de Neuropsicología, 3 (3), 58-67. 2001.

- Jumisko E, Lexell J, Söderberg S. The meaning of living with traumatic brain injury in people with moderate or severe traumatic brain injury. LWW; 2005. p. 42-50.

- Australian Bureau of Statistics. Disability, ageing and carers, Australia: Summary of findings. Australian Bureau of Statistics Canberra, Australia; 2019.

- Thurman DJ, Alverson C, Dunn KA, Guerrero J, Sniezek JE. Traumatic brain injury in the United States: a public health perspective. The Journal of head trauma rehabilitation. 1999;14(6):602-15.

- Faul M, Coronado V. Epidemiology of traumatic brain injury. Handbook of clinical neurology. 2015;127:3-13.

- Ownsworth T, Mols H, O’Loghlen J, Xie Y, Kendall M, Nielsen M, et al. Stigma following acquired brain injury and spinal cord injury: relationship to psychological distress and community integration in the first-year post-discharge. Disability and rehabilitation. 2023:1-11.